John H. Cochrane. "Macro-Finance." Review of Finance (2017): 945-985.

The author discusses different macro-finance models. He contrasts their strengths and weaknesses, suggests paths for further research, and even describes their potential in furthering macroeconomic research related to recessions.

To sample from the different preferences and market structures, he considers ten cases:

To sample from the different preferences and market structures, he considers ten cases:

- Habits

- Recursive Utility

- Long-run risks

- Idiosyncratic risk

- Heterogeneous preferences

- Rare disasters

- Utility non separable across goods

- Leverage; balance sheet; institutional finance

- Ambiguity aversion, min-max preferences

- Behavioral finance; probability mistakes

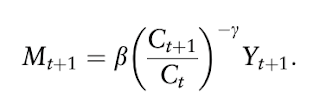

where C is consumption, gamma is the risk aversion coefficient, and Y represents additional risk.

In each case the author describes the central idea being that the market fears recessions as well as assets with decreasing values during recessions, and that the market's risk-bearing capacity falls during recessions as a result. Each case differentiates from the rest with respect to the exact state variable for expected returns including consumption related to recent values, news regarding long-run future consumption, cross-sectional risk, or leverage. The author reasons that these state variables are highly correlated and that each resulting model has helped to describe the same underlying idea of risk perceptions and how these perceptions relate to falling investments as well as our understanding of the mismatch between the riskiness of investment projects and the higher risk aversion of those who save. It is also noted, of course, that no model has succeeded in fully describing the equity premium/risk free rate puzzle as well as the excess volatility and business cycle risk premium.

Of the cases, particularly motivating is the idiosyncratic risk model. This model is similarly represented with a discount factor and a state variable,

with y representing the cross sectional variance of individual consumption growth. It's simplicity comes from the need to only assume a cross sectional variance process (y of t+1), however, this process must satisfy certain constraints for return predictability due to the model's simplicity. The volatility of cross sectional consumption must be large and vary greatly over time (as well as at the right times). While this isn't necessarily intuitive (empirical results aren't encouraging), the solution is to have a variance of future consumption that varies over time, or as the author states, "time variation in the conditional variance of the conditional variance of cross sectional risks". This has been explored, as in Constantinides and Ghosh (2017), with further opportunities for research relating to appropriate time-varying moments in micro data. Still, the model represents a simple explanation that people fear times of large idiosyncratic consumption risk (i.e. recessions) and this exacerbates a fear of poorly performing assets during these times. The author suggests this is in line with the reasoning of the other models discussed, with differences (such as the state variable being exogenous and requiring special assumptions) boiling down to esthetic preference of the researcher.

The author concludes by advocating for the consideration of macro-finance models and their potential usefulness in macroeconomic research related to recessions. He believes that research relating to macro-finance models may help to lessen the divide between macroeconomics and macro-finance due to the strong relationship between recessions and risk premiums, risk aversion, risk-bearing capacity among investors, as well as the shift to assets perceived safe during recessions. It will be our understanding of how risk perceptions affect investors, and not risk-free interest rates or inter-temporal substitution, that allow us to better understand recessions.

No comments:

Post a Comment